Lessons and Carols at CCSB

Throughout history, the Church kept Advent as a season of great solemnity - a time in which to meditate upon the ultimate issues of death, judgement, hell and heaven.

Advent, though, was also a time of great rejoicing, for Christ would come, not only as Judge, but also as Savior, and would usher in the Kingdom of God. Advent, therefore, provided a vivid preparation for Christmas. Processions from west to east, and the use of lights, spoke of the Church's hope in the coming of Christ - the Light of the world - to banish sin and darkness. Antiphons were sung, calling upon God to deliver his people, and readings from the Old Testament were seen as pointing to the fulfillment of God's purposes in Jesus.

This liturgy has been developed and used at the great English Cathedral at Salisbury and at St. James Cathedral in Chicago, and aims to recapture that Advent longing and hope. It begins in darkness with the Advent Responsory, in which Christ's coming is announced. The Blessing of Light follows, and, as the Service unfolds, the cathedral is transformed from darkness to light.

The service is structured around the Great "O" Antiphons of Advent, sung by the choir and congregation. (O Come, O Come Emmanuel.) These were sung originally as Antiphons to the Magnificat at the Evening Office from 17th to 23rd December, and have provided a rich source of devotional imagery in Advent. The readings and music serve to complement the Antiphons, and help us reflect on the theme of the Christ who comes to judge and save his people. The Service ends in confident hope in the One who is to come. Even so come, Lord Jesus.

The scripture readings come in pairs. An Old Testament reading speaks of God’s promise. A New Testament reading proclaims how the promise is being fulfilled in Christ. And each pair is accented by a musical response that heightens our expectation and invites our trust in the coming of Christ as Judge and Redeemer.

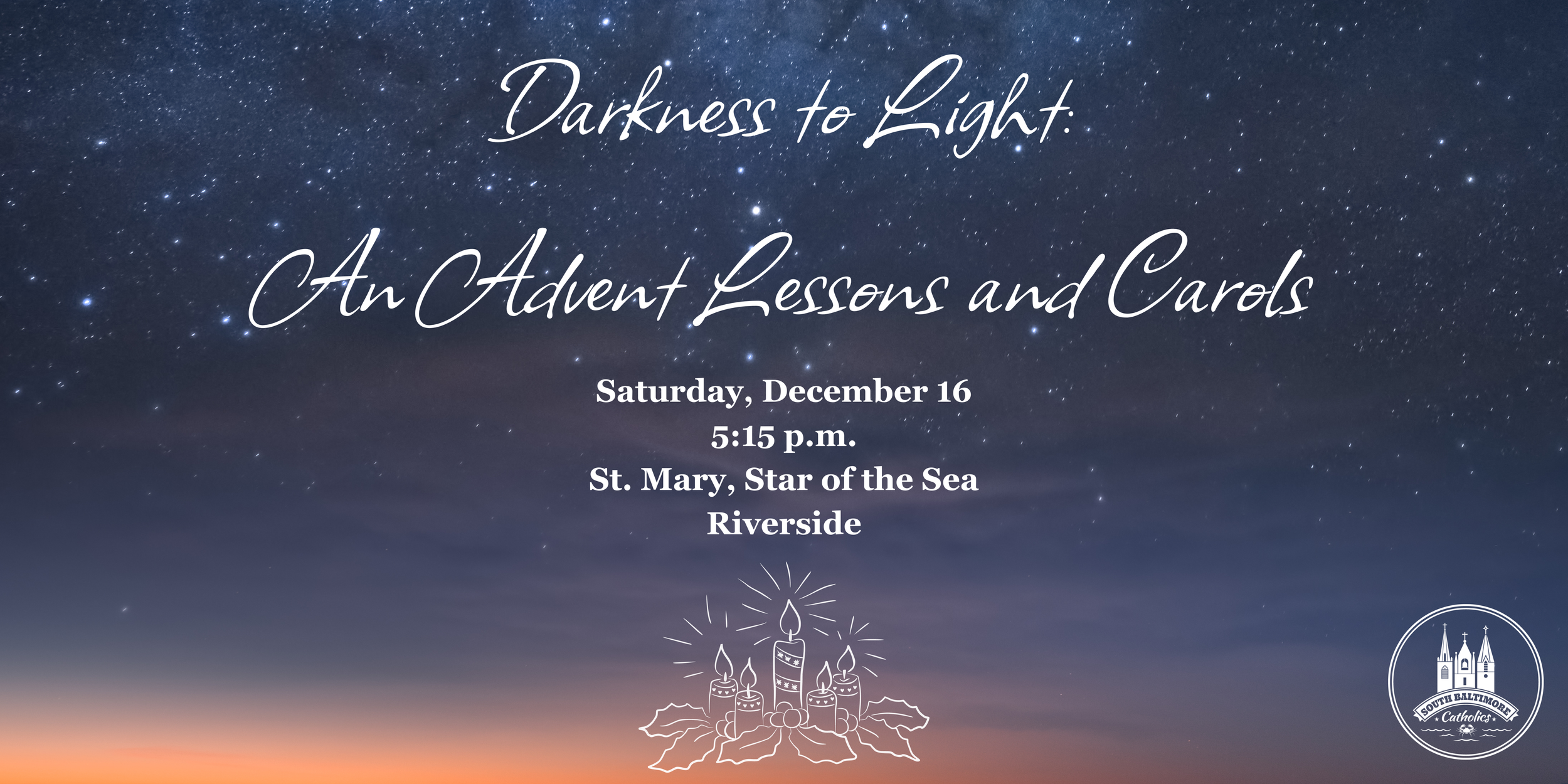

Darkness to Light: A Liturgy of Advent Lessons and Carols

A Reflection

Advent is, with Easter and Christmas, the season that most speaks to our contemporary human condition. It is a season that has long been symbolized by the lighting of the candles of an Advent wreath representing the four weeks of the Advent season and culminating in the lighting of the fifth principal candle at Christmas. No doubt this tradition reaches back into our Jewish past and the Feast of Lights at Hanukkah, and has been popular within Christian celebrations particularly in Germany and Scandinavian countries down the centuries. Today the Advent wreath has become a universal symbol, to be found in many households as well as in churches.

The lighting of a candle reminds us that though we live in a dark world at the heart of the Christian Gospel is a message of hope. Flickering and fragile though the light of a candle may be yet the flame of such a candle lights up a dark room. It represents that Light of the World which illuminates our world and our lives with its transforming radiance which guides us into all truth. It is in the belief that God is with us even in the darkness — as the story of Jesus will reveal as we travel the journey of his life from Advent to Pentecost — that many churches begin this Advent Season by lighting a single large candle in a dark church at the start of an Advent Procession. The candle recalls the hope incarnated in Jesus that shines in our dark world, as I have just described. And the procession reminds us that Christians are a pilgrim people, ever on the move for, as the Epistle to the Hebrews says: We have here no abiding city but we seek one to come.

Of course Christmas awaits us at the end of this four week season, and we will then be back in our comfort zone: back with the baby and hovering angels, the ox and the ass, the shepherds and their sheep, and the incense and the gold (let’s forget myrrh for a moment with its darker implications!) Christmas, profound festival though it is, as we celebrate the Word made flesh and dwelling among us, often triggers our sentimentality and a superficial optimism. We forget that, much as we enjoy Christmas, often to excess, many in our world live without the basic necessities we take for granted, and for whom life is often ‘nasty, brutish and short’. It was among them that Jesus was born, and for them he died. Just as we cannot celebrate Easter without plumbing the depths, as Jesus did, of Good Friday, so we cannot celebrate Christmas without the sobering preparation of Advent.

Advent is rich in music and verse, including some of the finest poetry in scripture, dominated by the prophecies of Isaiah and the heroic stories of John the Baptist and the Virgin Mary. For many ©St. James Music Press, 2016 — www.sjmp.com — Licensed permission to photocopy granted of us Advent’s rich texture is exemplified in the Advent hymns with their declamatory message and their thunderous melodies. But for all its plangent beauty Advent begins in darkness and silence, reminding us of the real world beyond the shrine, where God himself was content — indeed determined — to pitch his tent.

As well as preparing for Christmas Advent has traditionally focused on more sombre themes as well, reminding us not only of the first coming of Jesus, but also of his second coming when as the Creed rehearses ‘he will come again in glory to judge both the living and the dead’. This is a theme picked up in Thomas Cranmer’s peerless Advent Collect where he talks of Jesus who ‘comes at the last day in his glorious majesty to judge both the quick and the dead’. Some of our Advent hymns like ‘Lo he comes with clouds descending’ focus on the Four Last Things — death, judgment heaven and hell — adding a penitential note to our Alleluias. Though not much preached about these days those traditional Advent themes do concentrate on the ultimate things that confront us as human beings, and we need such opportunities as the Advent season provides to reflect on them. These themes reveal us — and indeed the whole of humanity — as we truly are. Not a pleasant sight, but extraordinary though it may seem, it is in us, — frail, wayward, prodigal humanity that we are — that God sees himself reflected and longs to get his own back — that is to bring us back home. That is why God, in Jesus, gave himself (emptied himself and was obedient even unto death is how St Paul puts it) so that all who believe should not perish but have eternal life.

Our world is dark — despite our human ingenuity and inventiveness — and our lives are dark as well, but year by year we light a candle in a dark room, as a sacramental affirmation that God has already lit a candle in our dark world. That light of the world has a name – his name is Jesus. ‘That light was the true light that enlightens everyone. The light shines in the darkness, and the darkness has never overcome it’. We will hear those words from St John’s Gospel again on Christmas Day. That is the Christian good news, that though our world is dark, a light shines. Its meaning is this: God loves us and he will never leave us. That conviction gives hope to our world and to each one of us. That is the message of Advent.

Thank God!

— The Rev’d Canon Jeremy Davies